The Role of US Investments for EU Technology Sovereignty

Dr Matthias Bauer, Director at ECIPE and Ms Dyuti Pandya, Junior Analyst at ECIPE

Industry data point to a considerable investment disparity between US and EU digital companies, underscoring the role of US tech investments in the EU’s Information and Communications Technology (ICT) sector and highlighting the mutual interdependence between the two regions. In this piece, we delve into the challenges the EU faces regarding ICT development and adoption, and the need to secure and maintain investments from US-based technology companies. Fostering transatlantic collaboration and deeper long-term partnerships would mitigate the EU’s internal challenges, enhance the EU’s much-needed digital transformation, and ensure its competitive stance in a growing global digital economy.

In 2020, while presenting EU strategies for data and artificial intelligence, the President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen said that Europe needs to be able “to make its own choices based on its own values, respecting its own rules”. In a similar vein, the President of the Council of the European Union Charles Michel argued that there is “no strategic autonomy without digital sovereignty.” These two statements have shaped the EU’s digital agenda in the past four years or so.

Invoking concepts of strategic autonomy and sovereignty, some EU policymakers have pointed to the perceived vulnerability stemming from digital services offered by companies headquartered outside the EU. In this context, political assertions underscore that EU’s reliance on the US for technology infrastructure and capital is gradually eroding its aspirations, sector by sector. Nevertheless, the argument concerning EU’s diminishing dominance can be recognised by its inherent structural deficiencies and the unforeseen consequences arising from ambitious EU policy initiatives. Such initiatives have continued to place EU behind US and China in the competitive race.

In a previous report for the European Parliament, Action Plan 1 in the report included building a European “firewall/cloud/internet” which would allow the formation of a European digital ecosystem. In a recent discussion involving Bruno Le Maire, Robert Habeck and Adolfo Urso – the competent Ministers for industrial and digital affairs of France, Germany and Italy, respectively – it was agreed that “EU’s industrial policy should integrate a well-targeted support for strategic industries”. In November 2023, the EU announced a funding of €85 million for advancing research in data and computing technologies. Additionally, a €206 million will also be allocated for research projects focused on enhancing Europe’s digital and technological competitiveness. The European Commission also approved the Important Projects of Common European Interest (IPCEI) Next Generation Cloud Infrastructure and Services (CIS) where seven Member States (France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, and Spain) will provide funds up to €1.2 billion to foster the development of European cloud. Such measure(s) indicates that to safeguard local technologies and promote innovation within EU, there is a need for an increased regulatory oversight, and more state aid, which potentially comes at the expense of limiting competition by reducing the presence and investments of foreign companies.

Yet, the robust presence and significant “sunk costs” associated with investments by US tech companies in the EU’s ICT sector mean substantial barriers to exit. The key to propelling the EU to the forefront of innovation lies in the sustained influx of US investments and the dependency on their infrastructure. The issue of the “White Knight Syndrome” with many EU companies has further exacerbated the investment divide, and the inability of EU firms to bridge this gap suggests that the resolution to the technology investment conundrum rests with US corporations.

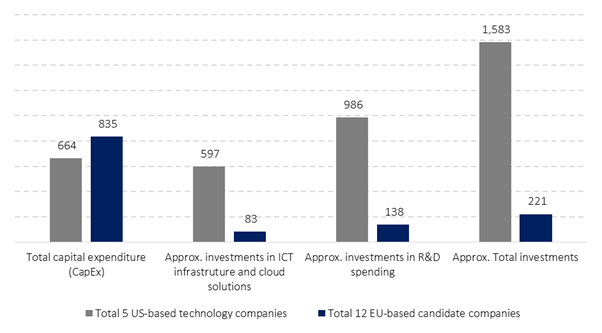

Data reveals that there is a significant investment gap of approximately USD 1.36 trillion between US and EU ICT companies (see Figure 1). This highlights the competitive edge which US firms hold over the EU firms due to their ability to invest heavily in ICT infrastructure including cloud and R&D. Forecasted scenarios, assuming the same growth patterns in the market, indicate an increase in the ICT investment by US tech companies. These investments are projected to grow to approximately USD 4.5 trillion by 2030, USD 25.6 trillion by 2040, and an astonishing USD 145.8 trillion by 2050.

The data is indicative of decisions made by US technology companies to invest strategically and significantly in EU Member States, where priorities in the recent years have shifted towards advanced ICT infrastructure and solutions as seen in cloud and AI, as well as increases in R&D spending in and beyond these areas. For instance, advancements within Europe’s cloud industry are predominantly propelled by three world-leading ICT providers (hyperscalers), collectively developing 70 percent of the Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS) market: Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, and Alphabet Google Cloud. The significant investments by these firms, underpinned by substantial revenues, serve as an effective barrier to exit, challenging conventional theories that perceive sunk costs as a deterrent to entering the market.

Figure 1: Development of Total ICT and Cloud-Related Investments, 5 US headquartered Technology Companies Vs. 12 EU-Headquartered Candidate Companies, 2005 To 2022, In USD Billion

Source: own calculations based on companies’ annual reports.

The influx of investments from US tech firms reflects a strategic commitment to the European market, and a long-term strategy for seeing the return on these investments rather than taking the decision of abandoning them. The inherent nature of technological advancements often involves sunk costs associated with long maturity investment returns. The investments in research facilities, manufacturing plants, and employee bases contribute to the mutual dependency between critical technologies sectors. These sectors further exhibit even deeper interdependence between the US and EU due to joint and interoperable technology standards, shared infrastructure, and collaborative research. Consequently, for US companies decoupling from these investments would mean losing access to a significant customer base, when there has already been extensive construction and operation of data centres by US companies across EU Member States.

The EU ICT sector’s growth underscores a vital integration with the global digital economy, leveraging American ICT services as a competitive asset to the EU economy. Notably, in 2020, US firms led in supplying 30 percent of the EU’s ICT imports, indicating that European business sought to use this as a strategic means to leverage competitive inputs. Investments by AWS, Google, and Microsoft have remained pivotal in developing the digital economies of not only emergent European markets, but also the emerging European markets like Poland and Hungary, with potential to boost the EU’s digitalization further if regulatory impediments are minimized. Without such acceleration, the EU risks achieving only 45 percent of its Digital Decade’s potential gross value added (GVA), possibly delaying its goals until 2040. The collaboration between US tech giants and EU companies is essential for the continent’s economic prosperity.

Political concerns over the presence of US tech companies

The relative underperformance of “native” EU-based tech companies compared to those from the US (and also China) explains much of why many European industries exhibit lower returns on capital, lower investment in R&D, and slower growth. In this context, substantial ICT investments by US tech companies across the EU Member States present an opportunity for transatlantic collaboration to drive the EU’s digital transformation, innovation, and structural economic renewal.

As an attempt to mitigate EU’s “reliance” on external tech entities, the Commission has strategically formulated, initiated and implemented a range of policies. These include, amongst others, taxes on digital services (DST), the Digital Services Act, the Digital Markets Act (DMA), Artificial Intelligence (AI) Act and the proposed EU Cybersecurity Regime for Cloud Services (EUCS). The enactment of such policies, either explicitly or implicitly (by design) target non-EU entities – particularly those at the forefront of global innovation – and such policies can have ramifications for European businesses that are both developing and utilizing cutting-edge digital technologies and services. The juxtaposition of investment discrepancies alongside emerging regulatory impediments suggests a trajectory towards the conceptualization of “splinternet,” an envisaged state wherein the networks within the sector undergo fragmentation and come under regulatory control and restrictions.

The EU’s strategy aims at reducing dependency on non-EU tech firms to enhance data portability, scalability, and deployment speed through a stronger regulatory framework, yet achieving the ambition of true autonomy seems distant from current realities. Concerns over data sovereignty and control, exacerbated by some extraterritorial powers of the US, have led to political hostilities towards cloud solutions provided by non-EU entities. However, addressing data sovereignty challenges requires more than just regulatory adjustments and legislative changes; the deep-seated interdependence between US and EU tech and technology-adopting sectors, including public services, further underscores the complexity of achieving such aims.

Notably, to comply with European data sovereignty requirements, many non-EU providers of digital services have introduced specialized cloud solutions to meet data sovereignty requirements. For instance, Google launched Google Cloud Sovereign Solutions in collaboration with various European companies, such as T-Systems in Germany, S3NS in France, Minsait in Spain, and Telecom Italia in Italy. Likewise, Microsoft introduced Microsoft Cloud for Sovereignty, offering residency choices across the entire Microsoft Cloud suite, encompassing Microsoft 365, Dynamics 365, and Azure. Additionally, Amazon AWS has guaranteed full compliance with European regulations for organizations utilizing AWS cloud services.

Regulating Cloud Services a Case in Point

The EU Agency for Network and Information Security (ENISA) is proposing a far-reaching European Cybersecurity Certification Scheme for Cloud Services (EUCS) to be established in the EU. According to the draft versions of the regulatory proposal, the proposed regime would by design prevent non-European vendors from providing many “high assurance level” cloud services in the EU. ECIPE research shows that foreign ownership and headquarter restrictions, local staff requirements, and data localisation would lead to significant losses in Member States’ aggregate economic activity and drive a big wedge between economic growth in the EU and the growth of non-EU economies.

According to a report in 2022, the Digital Decade in Europe could potentially unveil over 2.8 trillion euros in GVA, which would be equivalent to nearly 21 percent of the EU current economy. About 55 percent of the GVA is dependent on cloud computing. However, with an overly restrictive EUCS, it would become close to impossible for non-EU headquartered companies to provide advanced ICT solutions to many industries and public services.

Moreover, an overly restrictive EUCS would inadvertently limit market competition to favour Europe’s cloud industry which remains underdeveloped compared to its American counterparts. By imposing bureaucratic red tape on non-EU cloud companies, overly stringent rules would disrupt strategic partnerships with US firms, such as Deutsche Telekom’s collaboration with Google, Microsoft’s partnership with Proximus, AWS’ collaboration with T-systems, to name a few. It is likely that the regulatory move will also undermine EU’s ambitious efforts to diminish dependency on non-EU tech giants. From a broader and long-term perspective, these regulatory measures would also weaken the principles of international trade, especially commitments to non-discriminatory market access and the equitable treatment of foreign ICT service providers.

Conclusion

The growth of the ICT sector across EU Member States showcases the active involvement of and partnerships between European and US companies in digital services markets. The EU-US industry collaboration has resulted in unprecedented levels of technology adoption and diffusion in the Single Market, particularly within the emerging economies of Central and Eastern Europe. These developments are rooted in the EU’s historical commitment to open markets and non-discrimination as well as investments in innovation.

However, many political responses to the notable investment gap in the EU’s ICT sector, particularly in comparison to US tech investments, present a significant challenge for Europeans, hindering closer industry collaborations and slowing down the diffusion of technologies across the region. To bridge this gap and leverage more of the potentials advanced digital technologies offer, a more harmonious – less hostile – political relationship between the EU and the US is imperative.

Closer Transatlantic collaboration will foster geopolitical stability, spur innovation, and stimulate economic growth, while also safeguarding market and democratic principles. The EU-US Trade and Technology Council (TTC) can play a crucial role in this context, aiming for regulatory alignment and emphasizing the principle of non-discrimination to tackle economic and technological challenges effectively.