Evaluation Report on Amendments to the German Investment Screening Mechanism

By Jonas Fechter, University of Münster / CELIS Deputy Assistant Director

I. Legislative changes and reporting duties

Over the past couple of years, investment screening has become a central legislative instrument for promoting security and public order in many Western countries. When Germany first introduced its two-tier screening system in 2004 (military sector) and 2009 (non-military sector), this went against the then-existing zeitgeist of open markets and the free flow of capital and was, hence, met with scepticism if not outright criticism.[1] However, things have changed. Amidst growing geopolitical and geoeconomic tensions, the European Union has enacted the EU-Screening-Regulation that was first introduced in draft form in 2017 and entered into force in 2020. In the wake of this supranational piece of legislation, many Member States have introduced new screening mechanisms on a national level or amended and sharpened existing screening mechanisms.

Germany has also continuously adapted its screening mechanism reshaping it in line with the EU-Screening-Regulation. The German screening mechanism is based on the Foreign Trade and Payments Act (AWG), an Act of Parliament, and spelt out, in detail, in the Foreign Trade and Payments Ordinance (AWV), a regulation by the executive branch of the government. Until the enactment of the EU-Screening-Regulation, the German screening mechanism consisted of just a few rules set out in the AWV.[2] It has since been amended, in consecutive legislative waves, with the intention of bringing it into line with the EU-Screening-Regulation. Specifically, this was done in one Act of Parliament[3] and three executive regulations[4] in 2020 and 2021. With these changes, the scope and breadth of the screening mechanism were expanded significantly and made more precise.

Among other things, these legislative changes lowered the bar for administrative action in line with the EU-Screening-Regulation and significantly expanded the number of business sectors on which the government has to focus when screening a transaction. It also imposed notification duties on companies in a larger range of circumstances.

As these changes significantly deviate from the initial impetus of the European economic policy, both European and German legislators have imposed reporting and evaluation duties on the Executive in order to monitor the progress and efficiency of the new screening rules. According to Art. 15 EU-Screening-RL, the European Commission shall evaluate the functioning and effectiveness of the Regulation and present a report to the European Parliament and to the Council by 12 October 2023. According to § 82b AWV, the German Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Action, the chief administrator of the screening mechanism in Germany, must prepare a similar evaluation of the amendments to the German screening mechanism.

This evaluation by the Ministry, released on 6 October 2023, is the focus of this blog post. The report covers the legal and actual developments from 18 July 2020 to 18 July 2022 and was prepared with the help of the Federal Statistical Office of Germany. In addition to its own data and findings, the Ministry has requested information from the other federal departments involved in the screening procedures, as well as from the law firms that regularly represent investors and target companies and are, therefore, familiar with the subject matter of investment screening. All of the parties involved were sent questionnaires, the evaluation of which has revealed important facts that will guide the further development of the German and European investment screening environments and, moreover, identified elements for legislative changes.

II. Data on investment screening

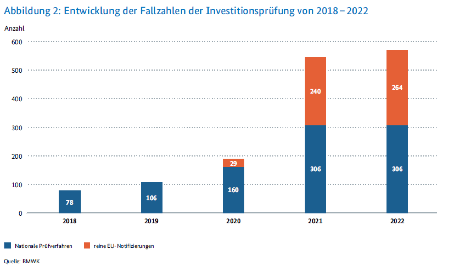

The evaluation set out to provide valuable data about the use and functioning of the German investment screening mechanism. The first finding of the report is that the overall number of screened transactions has tripled since 2018. This trend, according to the Ministry, can be attributed to the expansion of the screening laws. While the Ministry only screened 78 transactions in 2018, it logged 306 cases in 2022.[5]

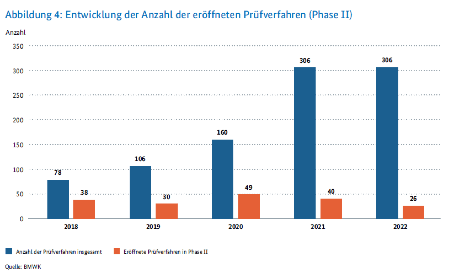

Surprisingly, while the overall number of cases has risen significantly, the German screening procedure is comprised of two stages and there has been a decrease in the number of cases entering screening Phase II. In the initial stage (Phase I), companies either notify the Ministry of a transaction or the Ministry is informed about the transaction through other channels. According to § 14a (1)(Nr.1) AWG, the Ministry then has two months to either clear the transaction or launch an in-depth screening procedure (Phase II). According to the report, the number of cases entering Phase II has decreased from 38 in 2018 to 26 in 2022. However, this may be due to the fact that the Ministry and the acquirer are now able to agree to extend the initial two-month deadline (§ 14a (5) AWG). This allows for more initial screening time before the formal screening process in Phase II commences.[6]

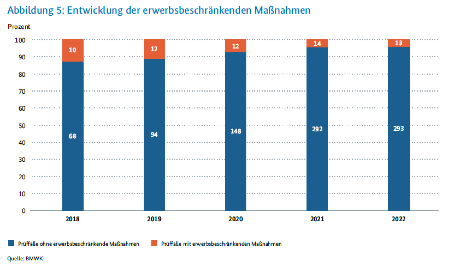

Furthermore, there has been no significant increase in the measures taken by the Ministry. If a transaction is likely to affect security or public order, the ministry can either suspend the transaction or take mitigating measures, either by imposing restrictive conditions unilaterally or by entering into a public-private contract with the parties to the transaction. The number of these restrictive measures has not increased much since 2018. However, the Ministry noted that 13 transactions were abandoned after the government expressed serious concerns over the transactions with the parties involved.[7] In addition, the tightening of the screening laws may have prevented investors from pursuing transactions in the first place.[8] Some such transactions might very well have been subjected to restrictive measures had they been pursued. Furthermore, the majority of transactions subjected to restrictive measures may have been addressed under the old law, too, although some would not have been notifiable under the old legislative framework.[9]

Finally, the Ministry managed to decrease the overall screening period. On average, cases entering Phase II took 216 days to be processed in 2019 but the average processing time reduced to 184 days in 2022. Similarly, cases that were only subject to Phase I took, on average, 38 days to be processed in 2022, although it took the Ministry, on average, 60 days to process them in 2019.[10] This improvement is chiefly attributed to an increase in the number of screening personnel at the Ministry.

III. Feedback from other departments and law firms

The other government departments involved in the screening process welcomed the legislative changes under evaluation. In fact, the legislative amendments have formally adopted the screening test from the EU-Screening-Regulation into German law. While the Ministry formerly had to prove that a transaction posed a “genuine and sufficiently serious threat to a fundamental interest of society”, it now (only) has to show that the transaction is “likely to affect security and public order”. Most government departments welcome this lowering of the bar for administrative action. However, they also noted that some terms in the law are unclear and confusing. This criticism was specifically directed towards some of the industry sectors set out in § 55a (1) AWV that are more likely to be subject to governmental screening. Furthermore, it has been suggested that the screening threshold should be reduced to 10 % of the voting rights in particularly sensitive sectors such as robotics, semiconductors, quantum technology and critical raw materials[11] and that the AWV should clarify that semiconductors include primary components such as wafers.[12]Finally, the departments noted that some critical investments are currently not subject to screening including greenfield investments, outbound investments, research cooperation and licensing agreements.[13]

Eight law firms participated in the Ministry’s survey. Of those, 87.5 % consider the legislative changes an improvement but note that it has significantly expanded the number of transactions that need to be reported. Nevertheless, 62.5 % believe that the changes made to the law strike the right balance between the need to protect national security and business interests. The law firms also asked for clarification regarding some of the terms in the law: for instance, they have found that it is unclear what constitutes the “development, fabrication or modification” of products particularly subject to investment screening in many transactions.[14] Furthermore, they have asked for more guidance on what constitutes an “atypical acquisition” under § 56 (2)(3) AWV, which could be provided, for example, via the FAQ published on the Ministry’s website.

1. The Costs of FDI-Screening

Screening foreign direct investment costs both the government and the parties to the transaction and the evaluation report contains the first comprehensive breakdown of the costs associated with the German screening mechanism. This part of the evaluation is based on data and calculations provided by the Federal Statistical Office of Germany and shows that the costs have risen sharply for the government. While in 2017, only seven officials across all federal departments were involved in the screening process, this number has blown out to over 42. This development can be attributed to the massive expansion of the screening sectors in § 55a (1) AWV. The overall costs for the federal government amount to 4,026,000 EUR (personnel cost: 3,676,000 EUR; cost of materials: 350,000 EUR).[15]

Likewise, investors had to deal with a sharp increase in the number of transactions being screened. Investors have to make notifications for transactions in more circumstances according to § 55a (4) AWV. However, the costs of the transaction have only risen moderately for each individual transaction.[16]

2. Overall assessment and policy recommendations

Based on this assessment, the Ministry considers the legal changes to the law of investment screening a success. Expanding the scope of the cases screened has led to better protection of national security and public order. Yet, simultaneously, the time it takes for each screening procedure has been brought down.

Furthermore, the Ministry has identified potential areas for further legislative action. Specifically, in order to prevent the circumvention of the investment screening mechanism, licensing agreements and greenfield investments may be screened in the future.[17] It has also been acknowledged that, given the feedback in the evaluation, “atypical acquisitions” need to be set out more precisely in the law. The same applies to some sectoral cases in § 55a (1) AWV. Given the sharp increase in cases and the fact that 86 % of the cases did not progress to Phase II of the screening procedure, the Ministry has suggested that the scope of the mechanism could well be tightened.

[1] Clostermeyer, Staatliche Übernahmeabwehr und die Kapitalverkehrsfreiheit zu Drittstaaten, 2011, p. 326 et seqq.

[2] The authority of the executive branch of government to issue an executive order was and is still established in the AWG.

[3] Erstes Gesetz zur Änderung des Außenwirtschaftsgesetzes und anderer Gesetze vom 10. Juli 2020 (BGBl. I S. 1636).

[4] Fünfzehnte Verordnung zur Änderung der Außenwirtschaftsverordnung vom 25. Mai 2020 (BAnz AT 02.06.2020 V1); Sechzehnte Verordnung zur Änderung der Außenwirtschaftsverordnung vom 26. Oktober 2020 (BAnz AT 28.10.2020 V1); Siebzehnte Verordnung zur Änderung der Außenwirtschaftsverordnung vom 27. April 2021 (BAnz AT 20.04.2021 V1).

[5] Chart No. 2 from the Ministry’s evaluation report. National screening procedures are colour coded blue, solely European notifications in orange: https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/DE/Publikationen/Aussenwirtschaft/evaluierung-gesetze-aenderung-aussenwirtschaftsgesetze-verordnung.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2, p. 15.

[6] Chart No. 4 from the Ministry’s evaluation report. Overall procedures are colour coded blue, those which also enter Phase II in orange:

[7] https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/DE/Publikationen/Aussenwirtschaft/evaluierung-gesetze-aenderung-aussenwirtschaftsgesetze-verordnung.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2, pp. 18, 35.

[8] https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/DE/Publikationen/Aussenwirtschaft/evaluierung-gesetze-aenderung-aussenwirtschaftsgesetze-verordnung.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2, p. 35.

[9] Chart No. 5 from the Ministry’s evaluation report. Procedures with no measures taken are colour coded blue, procedures with measures taken in orange:

[10] https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/DE/Publikationen/Aussenwirtschaft/evaluierung-gesetze-aenderung-aussenwirtschaftsgesetze-verordnung.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2, p. 19.

[11] It now stands at 20 % of the voting rights.

[12] This problem arose in the first ever court hearing related to an investment screening in a German administrative court, VG Berlin, Beschl. V. 27.01.2022, ECLI:DE:VGBE:2022:0127.4L111.22.00.

[13] See also, Fechter, National Security and the Quest for Technological Leadership, Law and Economics Yearly Review (11), 2/2022, pp. 182 et seqq.

[14] https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/DE/Publikationen/Aussenwirtschaft/evaluierung-gesetze-aenderung-aussenwirtschaftsgesetze-verordnung.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2, p. 24.

[15] https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/DE/Publikationen/Aussenwirtschaft/evaluierung-gesetze-aenderung-aussenwirtschaftsgesetze-verordnung.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2, p. 34.

[16] https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/DE/Publikationen/Aussenwirtschaft/evaluierung-gesetze-aenderung-aussenwirtschaftsgesetze-verordnung.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2, p. 30 et seq.

[17] See also Fechter, National Security and the Quest for Technological Leadership, Law and Economics Yearly Review (11), 2/2022, p. 182 et seqq.